I was awake—widely, cruelly awake. I had been awake all night; what sleep could there be for me when the woman I loved was to be married next morning—married, and not to me?

I went to my room early; the family party in the drawing-room maddened me. Grouped about the round table with the stamped plush cover, each was busy with work, or book, or newspaper, but not too busy to stab my heart through and through with their talk of the wedding.

Her people were near neighbours of mine, so why should her marriage not be canvassed in my home circle?

They did not mean to be cruel; they did not know that I loved her; but she knew it. I told her, but she knew it before that. She knew it from the moment when I came back from three years of musical study in Germany—came back and met her in the wood where we used to go nutting when we were children.

I looked into her eyes, and my whole soul trembled with thankfulness that I was living in a world that held her also. I turned and walked by her side, through the tangled green wood, and we talked of the long-ago days, and it was, “Have you forgotten?” and “Do you remember?” till we reached her garden gate. Then I said—

“Good-bye; no, auf wiedersehn, and in a very little time, I hope.”

And she answered—

“Good-bye. By the way, you haven’t congratulated me yet.”

“Congratulated you?”

“Yes, did I not tell you I am to marry Mr. Benoliel next month?”

And she turned away, and went up the garden slowly.

I asked my people, and they said it was true. Kate, my dear playfellow, was to marry this Spaniard, rich, wilful, accustomed to win, polished in manners and base in life. Why was she to marry him?

“No one knows,” said my father, “but her father is talked about in the city, and Benoliel, the Spaniard, is rich. Perhaps that’s it.”

That was it. She told me so when, after two weeks spent with her and near her, I implored her to break so vile a chain and to come to me, who loved her—whom she loved.

“You are quite right,” she said calmly. We were sitting in the window-seat of the oak parlour in her father’s desolate old house. “I do love you, and I shall marry Mr. Benoliel.”

“Why?”

“Look around you and ask me why, if you can.”

I looked around—on the shabby, bare room, with its faded hangings of sage-green moreen, its threadbare carpet, its patched, washed-out chintz chair-covers. I looked out through the square, latticed window at the ragged, unkempt lawn, at her own gown—of poor material, though she wore it as queens might desire to wear ermine—and I understood.

Kate is obstinate; it is her one fault; I knew how vain would be my entreaties, yet I offered them; how unavailing my arguments, yet they were set forth; how useless my love and my sorrow, yet I showed them to her.

“No,” she answered, but she flung her arms round my neck as she spoke, and held me as one may hold one’s best treasure. “No, no; you are poor, and he is rich. You wouldn’t have me break my father’s heart: he’s so proud, and if he doesn’t get some money next month, he will be ruined. I’m not deceiving any one. Mr. Benoliel knows I don’t care for him; and if I marry him, he is going to advance my father a large sum of money. Oh, I assure you that everything has been talked over and settled. There is no going from it.”

“Child! child!” I cried, “how calmly you speak of it! Don’t you see that you are selling your soul and throwing mine away?”

“Father Fabian says I am doing right,” she answered, unclasping her hands, but holding mine in them, and looking at me with those clear, grey eyes of hers. “Are we to be unselfish in everything else, and in love to think only of our own happiness? I love you, and I shall marry him. Would you rather the positions were reversed?”

“Yes,” I said, “for then I would make you love me.”

“Perhaps he will,” she said bitterly. Even in that moment her mouth trembled with the ghost of a smile. She always loved to tease. She goes through more moods in a day than most other women in a year. Drowning the smile came tears, but she controlled them, and she said—

“Good-bye; you see I am right, don’t you? Oh, Jasper, I wish I hadn’t told you I loved you. It will only make you more unhappy.”

“It makes my one happiness,” I answered; “nothing can take that from me. And that happiness he will never have. Say again that you love me!”

“I love you! I love you! I love you!”

With further folly of tears and mad loving words we parted, and I bore my heartache away, leaving her to bear hers into her new life.

And now she was to be married to-morrow, and I could not sleep.

When the darkness became unbearable I lighted a candle, and then lay staring vacantly at the roses on the wall-paper, or following with my eyes the lines and curves of the heavy mahogany furniture.

The solidity of my surroundings oppressed me. In the dull light the wardrobe loomed like a hearse, and my violin case looked like a child’s coffin.

I reached a book and read till my eyes ached and the letters danced a pas fantastique up and down the page.

I got up and had ten minutes with the dumbbells. I sponged my face and hands with cold water and tried again to sleep—vainly. I lay there, miserably wide awake.

I tried to say poetry, the half-forgotten tasks of my school days even, but through everything ran the refrain—

“Kate is to be married to-morrow, and not to me, not to me!”

I tried counting up to a thousand. I tried to imagine sheep in a lane, and to count them as they jumped through a gap in an imaginary hedge—all the time-honoured spells with which sleep is wooed—vainly.

Then the Waits came, and a torture to the nerves was superadded to the torture of the heart. After fifteen minutes of carols every fibre of me seemed vibrating in an agony of physical misery.

To banish the echo of “The Mistletoe Bough,” I hummed softly to myself a melody of Palestrina’s, and felt more awake than ever.

Then the thing happened which nothing will ever explain. As I lay there I heard, breaking through and gradually overpowering the air I was suggesting, a harmony which I had never heard before, beautiful beyond description, and as distinct and definite as any song man’s ears have ever listened to.

My first half-formed thought was, “more Waits,” but the music was choral music, true and sweet; with it mingled an organ’s notes, and with every note the music grew in volume. It is absurd to suggest that I dreamed it, for, still hearing the music, I leaped out of bed and opened the window. The music grew fainter. There was no one to be seen in the snowy garden below. Shivering, I shut the window. The music grew more distinct, and I became aware that I was listening to a mass—a funeral mass, and one which I had never heard before. I lay in my bed and followed the whole course of the office.

The music ceased.

I was sitting up in bed, my candle alight, and myself as wide awake as ever, and more than ever possessed by the thought of her.

But with a difference. Before, I had only mourned the loss of her: now, my thoughts of her were mingled with an indescribable dread. The sense of death and decay that had come to me with that strange, beautiful music, coloured all my thoughts. I was filled with fancies of hushed houses, black garments, rooms where white flowers and white linen lay in a deathly stillness. I heard echoes of tears, and of dim-voiced bells tolling monotonously. I shivered, as it were on the brink of irreparable woe, and in its contemplation I watched the dull dawn slowly overcome the pale flame of my candle, now burnt down into its socket.

I felt that I must see Kate once again before she gave herself away. Before ten o’clock I was in the oak parlour. She came to me. As she entered the room, her pallor, her swollen eyelids and the misery in her eyes wrung my heart as even that night of agony had not done. I literally could not speak. I held out my hands.

Would she reproach me for coming to her again, for forcing upon her a second time the anguish of parting?

She did not. She laid her hands in mine, and said—

“I am thankful you have come; do you know, I think I am going mad? Don’t let me go mad, Jasper.”

The look in her eyes underlined her words.

I stammered something and kissed her hands. I was with her again, and joy fought again with grief.

“I must tell some one. If I am mad, don’t lock me up. Take care of me, won’t you?”

Would I not?

“Understand,” she went on, “it was not a dream. I was wide awake, thinking of you. The Waits had not long gone, and I—I was looking at your likeness. I was not asleep.”

I shivered as I held her fast.

“As Heaven sees us, I did not dream it. I heard a mass sung, and, Jasper, it was a mass for the dead. I followed the office. You are not a Catholic, but I thought—I feared—oh, I don’t know what I thought. I am thankful there is nothing wrong with you.”

I felt a sudden certainty, and complete sense of power possess me. Now, in this her moment of weakness, while she was so completely under the influence of a strong emotion, I could and would save her from Benoliel, and myself from life-long pain.

“Kate,” I said, “I believe it is a warning. You shall not marry this man. You shall marry me, and none other.”

She leaned her head against my shoulder; she seemed to have forgotten her father and all the reasons for her marriage with Benoliel.

“You don’t think I’m mad? No? Then take care of me; take me away; I feel safe with you.”

Thus all obstacles vanished in less time than the length of a lover’s kiss. I dared not stop to consider the coincidence of supernatural warning—nor what it might mean. Face to face with crowned hope, I am proud to remember that common sense held her own. The room in which we were had a French window. I fetched her garden hat and a shawl from the hall, and we went out through the still, white garden. We did not meet a soul. When we reached my father’s garden I took her in by the back way, to the summer-house, and left her, though I was half afraid to leave her, while I went into the house. I snatched my violin and cheque book, took all my spare money, scrawled a line to my father and rejoined her.

Still no one had seen us.

We walked to a station five miles away; and by the time Benoliel would reach the church, I was leaving Doctors’ Commons with a special licence in my pocket. Two hours later Kate was my wife, and we were quietly and prosaically eating our wedding-breakfast in the dining-room of the Grand Hotel.

“And where shall we go?” I said.

“I don’t know,” she answered, smiling; “you have not much money, have you?”

“Oh dear me, yes. I’m not rich, but I’m not absolutely a church mouse.”

“Could we go to Devonshire?” she asked, twisting her new ring round and round.

“Devonshire! Why, that is where—”

“Yes, I know: Benoliel arranged to go there. Jasper, I am afraid of Benoliel.”

“Then why—”

“Foolish person,” she answered. “Do you think that Benoliel will be likely to go to Devonshire now?”

We went to Devonshire—I had had a small legacy a few months earlier, and I did not permit money cares to trouble my new and beautiful happiness. My only fear was that she would be saddened by thoughts of her father; but I am thankful to remember that in those first days she, too, was happy—so happy that there seemed to be hardly room in her mind for any thought but of me. And every hour of every day I said to my soul—

“But for that portent, whatever it boded, she might have been not my wife but his.”

The first four or five days of our marriage are flowers that memory keeps always fresh. Kate’s face had recovered its wild-rose bloom, and she laughed and sang and jested and enjoyed all our little daily adventures with the fullest, freest-hearted gaiety. Then I committed the supreme imbecility of my life—one of those acts of folly on which one looks back all one’s life with a half stamp of the foot, and the unanswerable question, “How on earth could I have been such a fool?”

We were sitting in a little sitting-room, hideous in intention, but redeemed by blazing fire and the fact that two were there, sitting hand-in-hand, gazing into the fire and talking of their future and of their love. There was nothing to trouble us; no one had discovered our whereabouts, and my wife’s fear of Benoliel’s revenge seemed to have dissolved before the flame of our happiness.

And as we sat there, peaceful and untroubled, the Imp of the Perverse jogged my elbow, as, alas! he does so often, and I was moved to tell my wife that I, too, had heard that unearthly midnight music—that her hearing of it was not, as she had grown to think, a mere nightmare—a strange dream—but something more strange, more significant. I told her how I had heard the mass for the dead, and all the tale of that night. She listened silently, and I thought her strangely indifferent. When I had finished, she took her hand from mine and covered her face.

“I believe it was a warning to us to flee temptation. We ought never to have married. Oh, my poor father!”

Her tone was one that I had never heard before. Its hopeless misery appalled me. And justly. For no arguments, no entreaties, no caresses, could win my wife back to the mood of an hour before.

She tried to be cheerful, but her gaiety was forced, and her laughter stung my heart.

She spoke no more about the music, and when I tried to reason with her about it she smiled a gloomy little smile, and said—

“I cannot be happy. I will not be happy. It is wrong. I have been very selfish and wicked. You think me very idiotic, I know, but I believe there is a curse on us. We shall never be happy again.”

“Don’t you love me any more?” I asked like a fool.

“Love you?” She only repeated my words, but I was satisfied on that score. But those were miserable days. We loved each other passionately, yet our hours were spent like those of lovers on the eve of parting. Long, long silences took the place of foolish little jokes and childish talk which happy lovers know. And more than once, waking in the night, I heard my wife sobbing, and feigned sleep, with the bitter knowledge that I had no power to comfort her. I knew that the thought of her father was with her always, and that her anxiety about him grew, day by day. I wore myself out in trying to think of some way to divert her thoughts from him. I could not, indeed, pay his debts, but I could have him to live with us, a much greater sacrifice; and having a good connection, both as a musician and composer, I did not doubt that I could support her and him in comfort.

But Kate had made up her mind that the disgrace of bankruptcy would break her father’s heart; and my Kate is not easy to convince or persuade.

At Torquay it occurred to me that perhaps it would be well for her to see a priest. True, Father Fabian had counselled her to marry Benoliel, but I could hardly believe that most priests would advise a girl to marry a bad man, whom she did not love, for the sake of any worldly gain whatsoever.

She received the suggestion with favour, but without enthusiasm, and we sought out a Catholic church to make inquiries. As we opened the outer door of the church we heard music, and as we stood in the entrance and I laid my hand on the heavy inner door, my other hand was caught by Kate.

“Jasper,” she whispered, “it is the same!”

Some person opening the door behind us compelled us to move forward. In another moment we stood in the dusky church—stood hand-in-hand in dim daylight, listening to the same music that each had heard in the lonely night on the eve of our wedding.

I put my arm round my wife and drew her back.

“Come away, my darling,” I whispered; “it is a funeral service.”

She turned her eyes on me. “I must understand, I must see who it is. I shall go mad if you take me away now. I cannot bear any more.”

We walked up the aisle, and placed ourselves as near as possible to the spot where the coffin lay, covered with flowers and with tapers burning about it. And we heard that music again, every note of it the same that each had heard before. And when the service was over I whispered to the sacristan—

“Whose music was that?”

“Our organist’s,” he answered; “it is the first time they’ve had it. Fine, wasn’t it?”

“Who is the—who was—who is being buried?”

“A foreign gentleman, sir; they do say as his lady as was to be gave him the slip on his wedding day, and he’d given her father thousands they say, if the truth was known.”

“But what was he doing here?”

“Well, that’s the curious part, sir. To show his independence, what does he do but go the same tour he’d planned for his wedding trip. And there was a railway accident, and him and every one in his carriage killed in a twinkling, so to speak. Lucky for the young lady she was off with somebody else.”

The sacristan laughed softly to himself.

Kate’s fingers gripped my arm.

“What was his name?” she asked.

I would not have asked: I did not wish to hear it.

“Benoliel,” said the sacristan. “Curious name and curious tale. Every one’s talking of it.”

Every one had something else to talk of when it was found that Benoliel’s pride, which had permitted him to buy a wife, had shrunk from reclaiming the purchase money when the purchase was lost to him. And to the man who had been willing to sell his daughter, the retention of her price seemed perfectly natural.

From the moment when she heard Benoliel’s name on the sacristan’s lips, all Kate’s gaiety and happiness returned. She loved me, and she hated Benoliel. She was married to me, and he was dead; and his death was far more of a shock to me than to her. Women are curiously kind and curiously cruel. And she never could see why her father should not have kept the money. It is noteworthy that women, even the cleverest and the best of them, have no perception of what men mean by honour.

How do I account for the music? My good critic, my business is to tell my story—not to account for it.

And do I not pity Benoliel? Yes. I can afford, now, to pity most men, alive or dead.

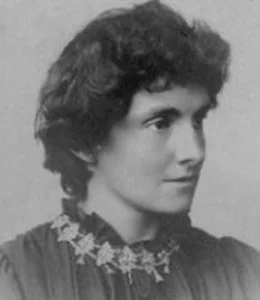

Edith Nesbit (15 August 1858 – 4 May 1924) was an English writer and poet, who published her books for children as E. Nesbit. Nesbit’s first published works were poems. Her first poem, “Under the Trees” was printed in March 1878. She authored and co-authored about 80 books for children, including novels, storybooks, and picture books. Nesbit also wrote for adults, including eleven novels, short stories, and four collections of horror stories.