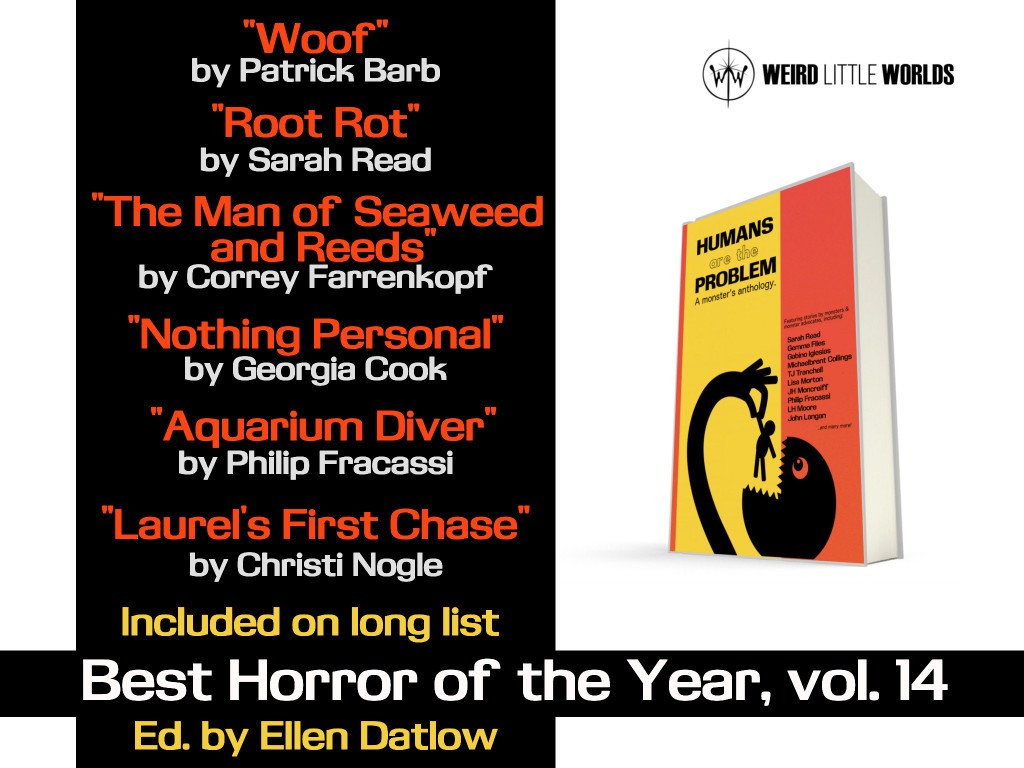

Inna Effress is a speechwriter, fiction writer, and poet who emigrated from Ukraine to the United States. Her work appears in numerous publications, including FOLIO, CutBank, Air/Light Magazine, Santa Monica Review, Swan River Press’s Uncertainties series, and Strange Tales at 30 (Tartarus Press), among others. Her fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and reprinted in The Best Horror Of The Year. Inna writes for grassroots organizations and leaders in California that are working to bring equitable outcomes to their communities. She and her husband, David Effress, live with their three kids, all creatives to the core.

***

Weird Little Worlds: What is one question that you get asked a lot? What is a question you wish people would ask you more?

Inna Effress: When people find out that I emigrated from Ukraine as a child, they ask me what I remember. Usually I tell them about my Kindergarten experience. At the time, Ukraine was part of the USSR, and I learned to speak Russian at school and at home. We kids were taught that Vladimir Lenin was our grandfather – we called him our “Dedushka” Lenin. Every day, we stood together, taking a solemn moment of silence under a portrait of him. Girls who were caught talking during silent time or nap time were called up to the front of the room, where a matronly woman yanked off our pants. Boys who misbehaved had their heads shaved.

That mass-produced image of Lenin has stuck in my mind’s eye through the years. Recently, through the research of a distant cousin in New York, I discovered that one of our family members was Lenin’s speech doctor after his stroke in 1924.

WLW: Please answer your second question above.

IE: People who know me sometimes ask me this, but I wish more people would talk me about motherhood. More than anything else, being a mom to my three teens is my reason for being. What makes me most proud, besides the kids’ kindness, is that all three of them are creators. My daughter’s a visual artist, film maker, and photographer, my older son scores music for film and composes pieces for jazz ensembles by working them out on his piano, and my youngest is consumed by robotics and building. I’m really lucky that I get to live with and learn from these inventive creatures with beautiful hearts!

WLW: Your day job is as a speech writer. What is one of the most moving speeches you’ve ever heard, and how has it impacted you?

IE: Elie Wiesel’s 1999 speech, The Perils Of Indifference. When I was in middle school, I learned details about the Holocaust and the Nazis by reading Wiesel’s memoir, Night. The book changed my life forever, and I began to study everything I could about the Holocaust. His speeches are some of the most quoted and taught in classrooms, from high school to the university level. This particular speech has memorable personal anecdotes, natural use of repetition, and most of all, in it he asks his audience a total of 26 rhetorical questions: (“Does it mean that we have learned from the past? Does it mean that society has changed? Has the human being become less indifferent and more human? Have we really learned from our experiences?” And so on…) The questions, I think, leave the listener no choice but to engage deeply with the speech and sit with the discomfort of it and of the meaning of indifference.

Q: You were born in the Ukraine, and that has had a huge influence on your writing. What is a special memory of your time in the Ukraine that informs your writing?

IE: I’ll answer this by pointing to a favorite Soviet literary influence, since I already did some reminiscing before reading this question!

One of my earliest memories is of lying in my bed every night as my mom read aloud Korney Chukovsky’s children’s poem, “Tarakanishche” (The Monster Cockroach). I couldn’t get enough of the feeling of terror that this story evoked, and this led to my obsession with other, dark Soviet mythologies. Baba Yaga, all the ghosts, the villains, the absolute madness, and eventually I fell in love with Gogol’s superstitions and legends, with the stories of Bulgakov, of Turgenev, and of course, Chekhov.

WLW: If you could invent an ice cream flavor based on your personality, what would it taste like?

IE: I had a fiancee once in my twenties whose favorite aunt, Lois, used to call me her sweet-and-sour girl. So I’d have to say my flavor would be a sweet and sour, saucy ice cream with a truth-bomb topping.

WLW: If you could go back in time and talk to the young Inna, what is one thing you would tell her? Would you warn her, uplift her, or both?

IE: Teenage Inna sure could’ve used some wisdom and hard insight into the future. I’d have a very serious sit-down with her and tell her to stop wasting time. I’d also tell her that nobody’s opinion matters but hers when it comes to choosing her path. It might be necessary to shake her by the shoulders a bit, just to get the point across.

WLW: What was the worst writing advice you ever received?

IE: Not to write in first person. Because of that advice, and the way it sank in, the closest I’ve ever come was a poem in first-person, but plural. The piece is about war and indoctrination, and it’s coming out soon, in FOLIO’s horror issue. Maybe seeing it out in the wild will give me the courage to get over my imagined limitations.

WLW: You’ve revealed before that you think you’re a slow writer. What advice do you have for other writers who don’t have a huge output of words?

IE: Honestly, the only thing that matters is to write, and to do it at your own speed and in your style. Don’t worry about what anyone else is doing. Comparing myself to other writers probably slowed me down even more, not to mention, it wasted a lot of scarce energy.

WLW: What’s your favorite piece of horror fiction, both book and movie?

IE: Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite is a movie I turn to again and again. Besides the incredible directing and its surprising turns, in a twisted way it reminds me of my own family, of immigration, of everything we have to do to lift each other up just to survive another day.

As far as literature, it’s hard to pick just one favorite, so I’ll mention my first love as an adult reader: Rikki Ducornet’s The Complete Butcher’s Tales. Creepy, evocative imagery, gorgeous, sensual language. Her sentences are to die for. I’ll never forget how this story collection transformed me, in a matter of days.

WLW: What will you be creating next?

IE: Both my grandfather and Elie Wiesel were born in Romania; both were forced to endure horrors while imprisoned in concentration camp. My grandparents met in a camp, and a year after liberation, my mother was born. I’m writing a book inspired by my mother’s father and his experience as a poker player given special favors by the camp guards, who had a bad card habit.

The Weird Team is comprised of several unhinged individuals that have a love of life and a lust for adventure. They scour the world to find the strangest, scariest, and most wonderful news in the universe.